In search of starlit skies: a trip to Black Rock Mountain State Park

and what we found instead.

Thickly blanketing the side of Black Rock Mountain Parkway, jewelweed buzzed with unseen bumblebees. A single bee, Bombus impatiens, broke away from the green, leafy cover. The bee’s low, musical buzz — like the humming of a baritone voice — became a high-pitched whine, reminiscent of a fly’s, when the bee’s face disappeared into a jewelweed blossom. The whine deepened to the musical, low hum again as the bee emerged from the flower and flew away into the green leaves.

I realized I was witnessing buzz pollination, a process in which bees vibrate their wings at a frequency which causes the flower to release pollen. Until that moment, I had no idea that jewelweed, Impatiens capensis, was a buzz-pollinated plant. As I write this, I realize that the specific epithet of our common Eastern bumblee — Bombus impatiens — is the same as the genus of jewelweed. BugGuide tells me this is not a coincidence; Bombus impatiens was named for these flowers.

Leaving the bumblebees, I continued to walk slowly up the hill in the fading daylight. A few stately, pink-stalked pokeweed plants rose from the midst of the jewelweed’s greenery. From that green also emerged early goldenrod, not yet in full bloom — tiny yellow-green buds and golden yellow flowers like beads along thin stalks standing tall and straight like candles in the growing dusk.

A silvery sound wrapped around me. Quiet music filled the air — cricket song like small, whispering bells, intermittently joined by the soft trilling of dark-eyed juncos. These shy, dark-gray relatives of sparrows and towhees appeared like pieces of shadow breaking away from the encroaching evening darkness, as they hopped along the road’s edges.

As I continued up the hill, I passed a few tall cutleaf coneflowers (Rudbeckia laciniata), yellow-green disc flowers surrounded by yellow ray flowers that jut out at varying angles. Above, higher up on the hill that lines the road, occasional sunbursts of an unknown species of woodland sunflower disrupted the darkness. A few Joe Pye weeds towered, dense bunches of small flowers forming clouds of pink mist. The hillside, however, was mostly green. The middle of August is an in between time, after spring and summer wildflowers have ceased to bloom, but before the peak of early fall flowers. Thus I was left to admire the hillside’s varying shades of green — bright and dark — and shapes of leaves. Cascading over rock face, ferns lay with the pinnate symmetry of feathers. Dark green, serrate-edged snakeroot leaves peeked out from below small white flowers. Along the road on short sapling stems, young locust trees stood with leaves round like coins, their surfaces decorated by the white scribbles scrawled by the mouths of leafmining insects.

The first time I visited Black Rock Mountain State Park, nearly two years ago, early fall flowers were in full bloom. In my memory of that visit, on September 5, 2022, a dark road wove and curved up the mountain, walled on either side with flowers, mostly yellow and white. These were the predominant flowers — Ageratina altissima (White Snakeroot) and Impatiens pallida (pale jewelweed, yellow where its more common relative, Impatiens capensis, is orange with spots, like a floral cheetah.) This was my introduction to Black Rock Mountain Parkway, the first place in Georgia where I saw these two species, plants I associated with another place and time.

I grew up in Northwestern New Jersey, not far from the Appalachian Mountains, and within view of a lake. Jewelweed lined the path along that lake’s shore, where I often took walks with my friends. White Snakeroot cascaded down the hillside of my next door neighbor’s yard. The small, white flowers of this plant cluster in round, white flower heads, which rest atop green branching floral stems (pedicels.) Up close, these flower heads are inornate white circles. But the effect of many hundreds of plain white flowers looked, to me, like lace.

On that first visit in September 2022, I parked the car in the first spot I could find, to walk along Black Rock Mountain Parkway and get closer to those flowers. I have now seen those flowers elsewhere in Georgia, but at that time, nine years after moving to Georgia and thirteen years after leaving New Jersey, this was like walking through a memory.

Black Rock Mountain State Park has the highest elevation of any Georgia state park. It rests on the Eastern Continental Divide, as signs throughout the park frequently remind you. The mountain is named for the biotite gneiss, a dark metamorphic rock, found on the mountain. In the mountains of Rabun County, Georgia’s northeast corner, it seemed a perfect spot to see the Perseid meteor showers. Last week, nearly two years after that first trip to Black Rock Mountain, I returned with my husband to belatedly celebrate our anniversary and try to see those meteor showers.

We arrived at one of the park cottages in the early evening, surprised to find no screen enclosing the porch. “What about mosquitoes?” we said. Looking for a silver lining, I thought that, without a screen, I might attract some interesting moths to the porch light. (I did, and best of all, there were no mosquitoes.)

Red-eyed vireos sang as we unpacked the car, back and forth, their high, repetitive song two three-note phrases. “Where are you? Here I am!” is the typical mnemonic for the red-eyed vireo’s song.

On such trips, I often try to pack every moment with a hike on a new trail or a visit to somewhere within driving distance. This time, instead of trying to explore as much space as possible, I focused on the area around our cottage. I explored the area around the cottages and walked along the section of Black Rock Mountain Parkway that ended at the cottages. At night, I turned on all of the porch lights and waited. I was not disappointed; moths and crickets appeared.

Around 2am of our first night at the cottage, my husband and I decided to head to the overlook next to the Visitor’s Center, where the park rangers had suggested we might see the meteor showers. We lay on the biotite gneiss and stared up at the sky, but saw nothing. Perhaps the lights from the town below were too bright. We got in the car and headed for Black Rock Mountain Lake, where the park rangers suggested we might also try to look for meteors.

At the lake, we parked by the pier, as the park ranger suggested, and lay on our backs looking up at the sky. Purple-black clouds swirled around the starlit darkness.

“I can’t tell if I saw a meteor or if it’s just eye floaties,” said my husband.

A few minutes later, I was jarred awake. “Did you see that?” he asked.

“Huh? I think I fell asleep.”

Over half an hour or so, we saw a few falling stars, but the clouds hid most of the meteor shower from view.

The next night, our second and last night on the mountain, clouds fully covered the sky. We did not see the Perseid meteor showers this time.

But what we did see was no less exciting.

That first night, slowly driving down the dark road to Black Rock Mountain Lake, movement caught my eye.

“Watch out!” I warned. “For that…cat?”

The car’s headlights illuminated a small creature with pointy ears.

“That’s not a cat! That’s a fox!” my husband exclaimed.

“I’m going to try to take a picture!” I fumbled for my camera, only to discover I’d left the memory card back in the cottage. I scrambled to turn on my phone camera and zoom in.

“Is that a fox?” one of us said.

“Maybe it’s a coyote,” I said. “I’ve only seen a fox once, and that was in New Jersey, a long time ago.”

At the same moment, we both came to the same, sudden conclusion. “Is that a dog?”

“Are we looking at chihuahua?”

“It doesn’t have a collar…”

The creature turned to the side and revealed a gray back and bushy tail. Definitely not a chihuahua. It was a gray fox.

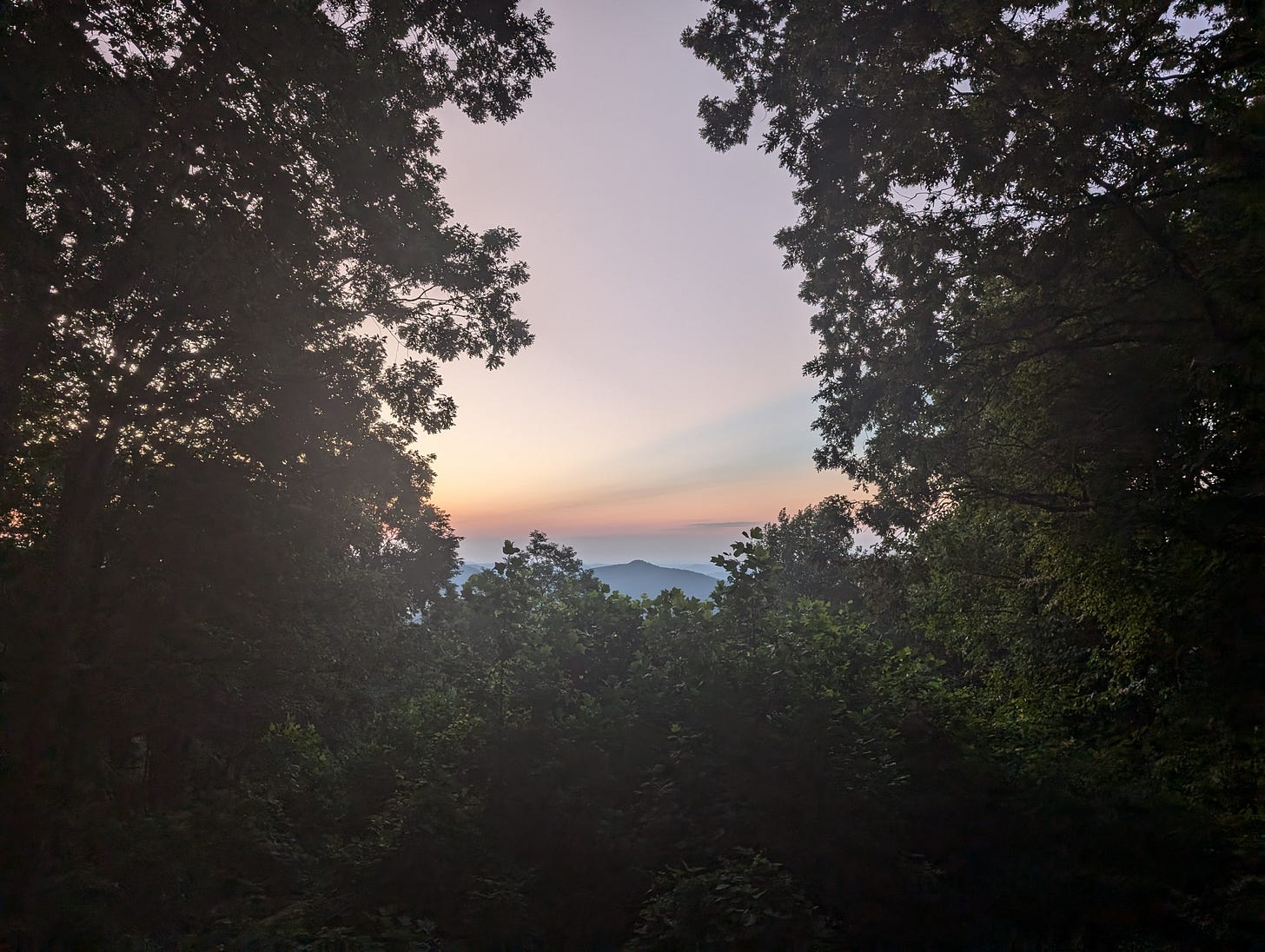

In the mornings, we sat on the back porch looking east towards a mountain view. Jewelweed grew in a thick border beyond the porch, with bumblebees buzzing from flower to flower. From the trees, I heard a ringing birdsong that I could not immediately recognize. It took me a moment to place it as a hooded warbler, whose playful, bouncy song I often hear in the spring closer to home. The tune was the same, but here at Black Rock Mountain, the voice was different — sparkling, bell-like, silvery like the crickets and the juncos I had heard in the evenings.

On our last morning, red-eyed vireos joined the hooded warbler, calling back and forth across the forest. Even their voices sounded silvery, a bell-like, “Where are you? Here I am.”

We stayed on the porch until the last possible moment. Just before I turned to go, I watched a spicebush swallowtail flutter over the jewelweed — an arcing flight that was slow, but not lazy; it was elegantly unhurried.

We bid the cottage goodbye and headed back down the mountain, back to Atlanta — towards mosquitoes, heat, and home.

A few more photos from the trip:

What a beautiful state park! My husband was working on WV/OH this week and sent me photos of jewelweeds! I was jealous! So many wonderful eastern species we don't have here in Texas. The fox story was really cute!