Stepping outside into a frosty Saturday morning, I heard a series of small sounds — staccato scratchy tapping somewhere near the ground. I glanced at the frost-laced leaves thickly blanketing the sleeping garden, expecting to see the movement of some creature under the dense cover, but the leaves were still.

Tiny specks danced down through the air in front of my eyes. Could it be snow? It was certainly cold enough. Perhaps the sound I’d heard was falling snowflakes slapping the stiff, frozen leaves.

I looked up. Not a single cloud interrupted the blue of the sky, not a single cloud from which precipitation could fall. As I walked through the yard, the sound quieted and soon ceased. As I traveled back towards the back porch, the sound resumed. Then I understood — thousands of tiny seeds had been falling from the sweetgum tree near the porch, quietly tapping as they landed on the leaves, stones, and soil below.

I stood under a sunset of hundreds of stars — the five-pointed leaves of sweetgum still not fallen or faded to brown, but painted with swirls of dark red, orange, gold, violet, and even green. Blue light — the bright sky — peeked out from the sharp-cornered spaces between leaves. Silhouetted as dark shadows, the sweetgum’s compound fruits — many capsules arranged into spiky brown spheres — hung like starburst ornaments from the branches. From these spiky gumballs, winged seeds fell, along with pale beige specks of chaff that floated like the snow flurries it resembled in size and shape. Collected on the ground, the chaff looked like a lot of spilled cereal — like whole wheat bulghur or very small steel cut oats. Flat, flaky, and shaped like narrow ovals slightly tapered at one end, the black and tan seeds looked like the shed claws of some creature from the sky.

The only creatures in the sky were blackbirds. With a chorus of staccato scratchy chirps and chatters, they swept across the unblemished blue and descended upon the backyard. Many foraged on the seed-covered ground; many crowded the sweetgum tree, poking sharp bills among sharp spikes of the capsules to eat the seeds that had not yet fallen. Above the chatter rose one bird’s high voice, calling out with a creaky squeak like an old pair of scissors snipping and cutting through the air like fabric — not to destroy, but to create, to shape it into a new form. The flock departed shortly after, leaving only shadow and seed capsules in the sweetgum — or so I thought, until one shadow broke away from the starry rainbow, a shadow that soon formed into a winged silhouette. A few stragglers that had camouflaged as gumballs emerged from the sweetgum canopy to soar across the sky and catch up to the flock.

It is the time of year I call The Brown Season, a time of few flowers and fewer insects. The leaves that still held on to bright colors through Thanksgiving are brown now; what remains on the post oak has lost its mottled green and orange, and the hickory no longer blazes with bright yellow, but rather clings to a few brittle brown leaves, papery and curled inward as though hiding from the cold and gloom. The asters have turned to seeds and pale gray fluff. The hard frost arrived and killed the last of the flowers; the salvia no longer glows indigo above green leaves. Instead, a few dark, dull purple blooms, dead and dry, hide among crinkled leaves turned a dark, charcoal gray with just a hint of green to their somber shade. In the trees, upon the ground, everywhere I look is brown, brown, brown. The colors of summer and fall have faded, drained by the darkness of cold, short days, leaving behind joylessness — a mix of melancholy and anhedonia. Brown, brown, brown. And gray – gray skys, gray trees, gray stones. And the black of winter nights, the black of shadow, and the black of bare trees against an overcast sky, tracing intricate patterns with their interwoven branches.

But the Brown Season is more than a rainbow of neutral tones. The water oak will hold its leaves and keep them green well into winter. Tiny chartreuse aphids will walk on the undersides of those leaves and feed upon them in January. American holly, mountain laurel, lobolly pine, and other evergreens will break up the beigeness. Violets and other small perennials will keep their green and might even produce a few out of season flowers. By February, blueberry bushes and their relatives begin to bloom, producing pale pink bells visited by small, fuzzy digger bees. Rusty orange comma and question mark butterflies will emerge on warm days.

While the salvia has frozen to the color of shadow, male bluebirds bring their ultramarine glow to the garden. The sky itself glows blue; on Saturday, as I’ve often observed on cold days, the sky shone like a sheet of blue metal. In the past, I’ve compared water that reflects the sky to metal, a shiny, silver-blue mirror, and as it flows over rocks and distorts the reflection, it is like crinkled tinfoil. On these cold, clear days, the sky reminds me of that water, but smooth, shining like a reflection on sun-brightened water. Late Saturday afternoon, the sky was so bright it hurt to look at, like the sharp glare of sunlight on a solid puddle of ice.

The steadfast blue jays, too, bring color to the drab Brown Season landscape, as do the reliable cardinals. Deep red, too, can be found in the throat of the yellow-bellied sapsucker, a winter visitor to this region. Red-winged blackbirds, too, gift us with flashes of crimson edged with a stripe of yellow. Yellow can also be found in the feathers of pine warblers and the tiny trumpets of Carolina jessamine, which I’ve seen blooming as early as January.

Even the brown is not so bad; it comes in a variety of shades and shapes, as in the stripes and curves patterning the plumage of female red-winged blackbirds, brown thrashers, hermit thrushes, and the myriad sparrows that winter here in the Southeast. Sunday morning’s garden was graced by a brown creeper, a shy, small bird who slowly climbs up the trunks of trees, blending in with the bark. I marveled at the marbled earth tones that swirled down the brown creeper’s back.

Even the dormant perennials, fields of dry stems standing in tall rows, leaves shriveled, colorless fruits cast in the shape of the flowers that once were, even these crowded ghosts of wildflowers are lovely. They capture the pale winter sunlight, the pale, wispy fruits of boneset clutching light between each thin thread, creating a glow like hundreds of tiny, small spheres atop each stem — hundreds of tiny suns. The Brown Season is a time of light and shadow, of texture and shape and of noticing how these all interact.

It is a time to slow down, reflect, to review the pictures, writing, and memories of brighter months. A time for reading and learning, for research and planning future adventures. A time to cover distance, to hike without becoming overwhelmed by the variety of sights. A time to focus on the landscape, its bones and stones. A break from the relentless heat and humidity of Southeast summers. A time to flip logs and notice what lives there, to admire millipedes and other overlooked, less loved creatures. A time to appreciate what green persists. A time to notice sound — the songs not just of birds but of wind and water. A time to look and listen for sandhill cranes. It is the time of winter waterfowl (aka Weird Duck Season) — in the absence of flowers and insects, winter gifts us with buffleheads, green- and blue-winged teal, redheads, pintails, and hooded mergansers. There are many ways to survive the Brown Season, to get through just three months of muted gloom, until the end of February, when spring ephemerals begin to burst from the soil, harbinger-of-spring and trout lilies and even some trilliums cover the earth, disrupting the endless carpet of brown leaves with bright patches of color.

UPCOMING EVENTS

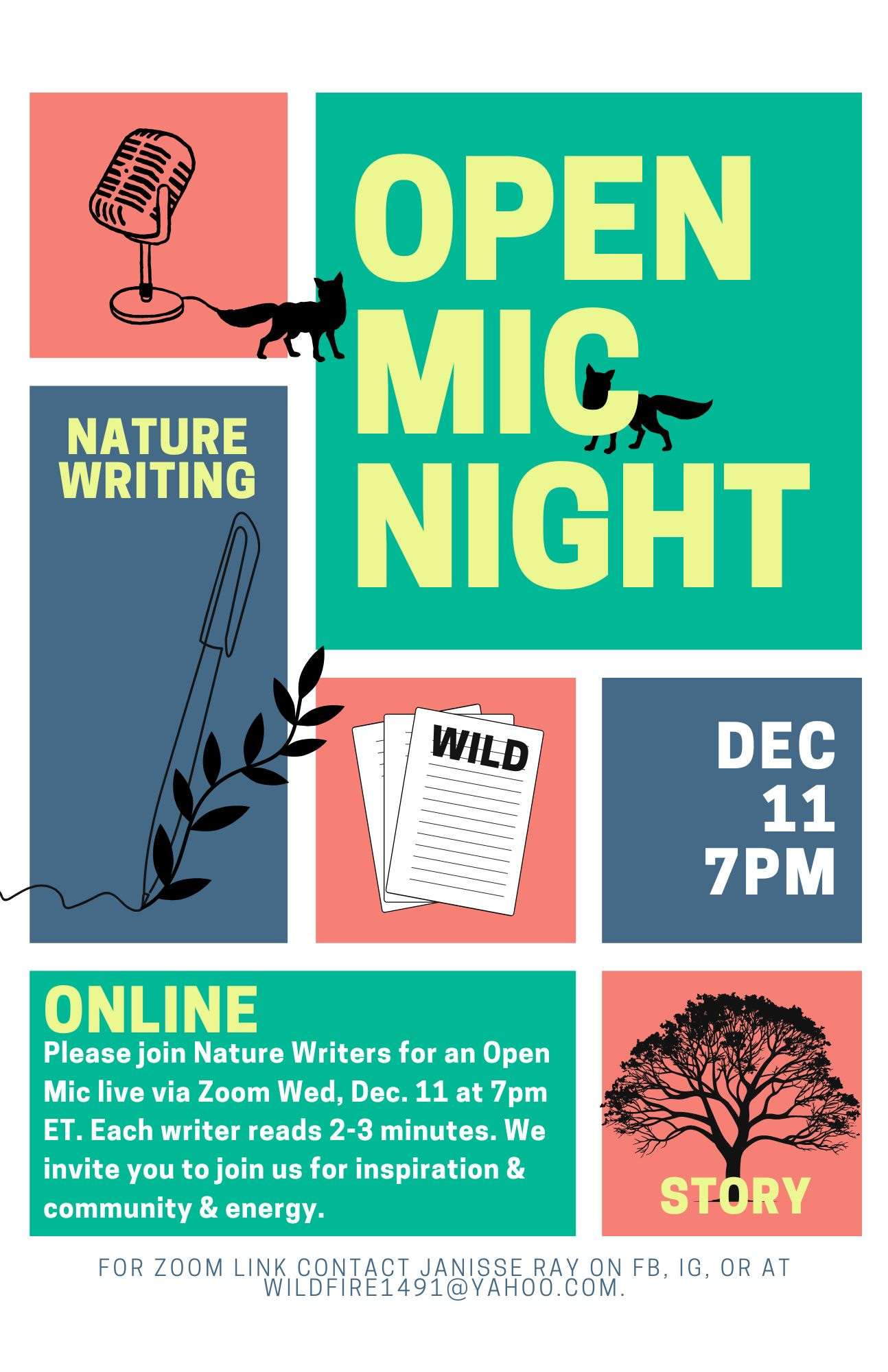

This Wednesday, December 11th, at 7pm EST on Zoom is the Open Mic Night for the Nature Writing Masterclass I took this fall with Janisse Ray. The event is open to the public, so if you would like to attend, contact me or Janisse for the link! (See information in the graphic below and in the alt text.)

Sarah, first thank you for posting the notice about the Open Mic. Then let me say how beautiful is this meditation on winter's brown. You are incredibly attuned to the wild world, and you notice so much. And you write beautifully about it. I'm so glad to know you.

Oh Sarah! This one took my breath away! I could FEEL the details in your noticing. I gophered in the woods today seeking embellishments for my Christmas mantle. I admired the turkey oaks still clinging to their mottle-colored leaves. I thanked each tree which allowed me to take snippets…pine, cedar, & holly. And I gathered dried grasses with fluffy tufts of seeds & stems with brown coins on it (reminds me of eucalyptus). It was a lovely afternoon, indeed. Thanks for appreciating the brown with me. 💜