Signs of Life Upon a Stone

Close-up looks at lichens in the Rocky Mountains on a cold December evening

In the last hour of the fading day, the vivid, bubblegum pink caught my eye. Next to the trail, a stone lay, a mix of orange-tan rock with pieces of sharp-edged, sharp-cornered pink — rose quartz, perhaps? I dropped to the ground for a closer look, resting my bag, camera, and binoculars carefully on a dry patch of rust-colored pine needles. Cold rushed into my knees, an icy, metallic feeling just shy of pain; it passed through the fabric of my jeans from the snow and the mud I knelt upon. I did not care. On a section of trail where signs of life had been sparse — no birdsong, a single squirrel, the flowers parched and pale like the meadow’s bones — here I found at least a dozen species of lichen, each one at least two species of fungus and photobiont, on just one stone.

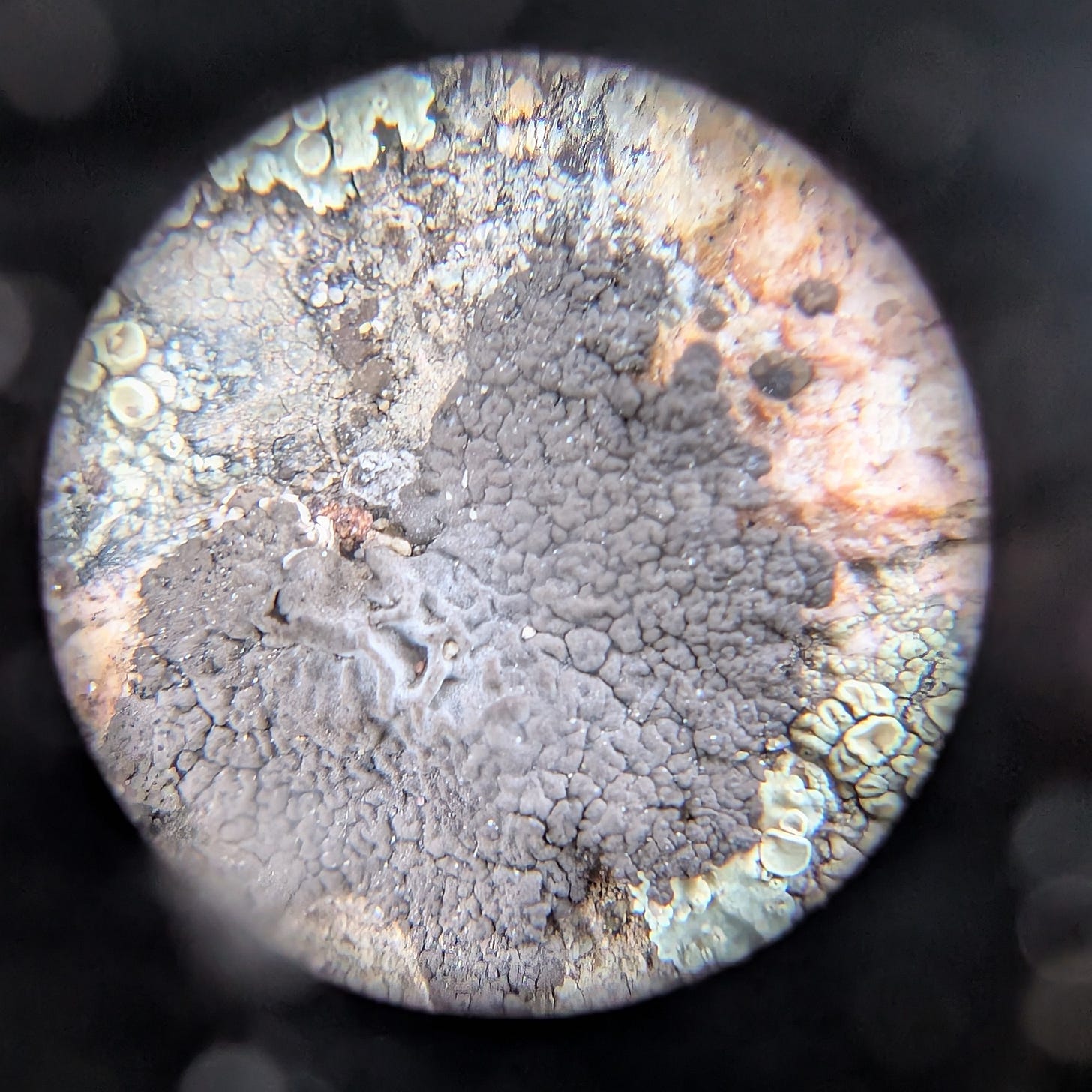

Pale turquoise rosettes and snowflake shapes, starbursts edged with lace; root-like rhyzines fastened foliose lichens to the rock’s surface, like leafy brooches pinned to a decorative pillow. Fan shaped and nearly black, a few rock tripe (Umbilicaria sp.) adorned the rock as well; the dark lichen’s thallus bent and wrinkled into thin, branching lines like veins. Gray crustose lichens splotched the stone’s surface like paint, their irregular shapes bordered with black and their thin thalluses fractured into tiny shapes that reminded me of scales.

Atop a flowery turquoise thallus, orange discs, some edged in blue-green, and some folded inwards, gathered in groups. Similar lichens, pale yellow-green, also formed on this rock, with discs not orange but the same green as the rest of the lichen’s thallus. These were rock-posy lichens, genus Rhizoplaca. I’ve tentatively IDed the orange-disced rock-posy as R. chrysoleuca, Orange Rock-Posy, and the green-disced as R. melanophthalma, Green Rock-Posy.

A splash of dark marigold on a nearby rock brought me a few feet further up the trail. Upon closer inspection, this orange lichen was thin, lacy branches radiating from a center of orange discs. From the color, I recognized it was a member of family Teloschistaceae, whose Southeastern members include the sulphur firedots that speckle Atlanta sidewalks and fluoresce under UV light. I returned to my bag and fished out my UV flashlight. Unfortunately, its battery was dead!

I have tentatively IDed this orange lichen as Rusavskia elegans, Elegant Sunburst Lichen. In the photo above, it rests upon a rock totally covered with lichen — gray, scaly, crustose lichens; toothpaste blue leafy lichens; and dark brown cobblestone lichens (tentatively IDed as Acarospora sp.)

For a full half hour, I covered a small section of trail, moving from rock to rock, examining lichens with my eyes, my phone’s camera, and a hand lens. Soon I came to a group of rocks I would describe as “shelfy.” As I’ve mentioned before, I am bad at geology, though I am trying to learn. I do not know the correct term for a rock that seems to be made of multiple rectangle-ish layers, like a stack of shelves, so I describe them as “shelfy.” (Please, if you know what the correct word is, tell me!)

On these rocks, I found more of the bright, dark orange sunburst lichen, as well as other bright colors of lichens comprised of many small discs or cups. The most abundant were bright yellow discs that I’ve tentatively IDed as Candelariella and dark, rust-red discs that I still haven’t identified. (I’ve guessed they are in the family Teloschistaceae, like the sunburst lichens.) These shelfy rocks bore more of the rock-posies, pale gray scale-like crustose lichens, and scattered speckles of dark brown and black discs that I had found on the smaller rocks.

I climbed to the top of a nearby hill, crowned with a complex of boulders, amidst junipers and pines. I crept along the edges of the boulders, peeking through my hand lens at stone surfaces. The most striking find among the boulders was bright yellow splashed upon the rock’s surface, a large thallus of nearly neon yellow bumps. I’ve tentatively identified this as Pleopsidum flavum, Gold Cobblestone Lichen.

Here I heard my first birds of the hike; looking up, I saw them — mountain chickadees flitting in and out of the shadowed boughs of Ponderosa pine.

When I had started out on this short, evening hike, birds had been my goal. While winter lacks flowers, it still offers birds, and winter is an opportunity to see species that one might not see in other seasons. In traveling to Colorado for Christmas, I expected to add quite a bit to my life list. I studied eBird and iNaturalist weeks in advance and tried to mentally fix the search images — Steller’s jay, Canada jay, Western bluebird, mountain bluebird, Townsend’s solitaire, redpoll, American dipper, American tree sparrow — yet around our cabin, I’d only seen pygmy nuthatches.

But winter provides. In the near silence of the chill evening, among faded grasses and skeletal wildflowers, I found color and life on the stones. I remained outside with the stones, the mountains, the few chickadees, and the lichens, until the sun set. Just before darkness began to drop over the mountain, I came across a herd of mule deer foraging near our cabin. Among the pale plants, winter provided for the mule deer. I watched them until they crossed the road and climbed up into the hills beyond. I turned towards the cabin and climbed up a different hill and then the porch stairs. Just before I went indoors, I looked out across the mountains, where houses were visible as their inhabitants turned on the lights. The windows were tiny squares of glitter scattered across the mountain, like speckles of mica sparkling the surface of a stone.

LICHEN BASICS AND REFERENCES

Lichens are the symbiosis of a fungus and a photobiont — an alga or cyanobacteria — that are named for the fungus. The photobiont provides itself and the fungus with food through photosynthesis. Lichens are found on every continent and can grow in far less hospitable places than other organisms, such as rocks, sidewalks, metal signs, and the handle of a tea kettle on my back porch. They are also found on organic substrates, such as leaves, tree bark, and moss.

Learning to identify them, particularly to species, can be tricky. Some can only be identified through microscopy, dissection, and/or chemical tests. Many can be identified with one’s eyes, camera, and a few inexpensive tools — a hand lens and a UV flashlight. To get started, I recommend using iNaturalist both to browse local lichen observations and to post your own, but keep in mind that its Computer Vision is overconfident at identifying lichens to species.

I’ve been asked about lichen field guides; these are not as common as field guides to birds, plants, or larger mushrooms. However, local resources exist online, such as the Georgia Lichen Atlas. For this post, I double-checked some of my terminology with Urban Lichens: A Field Guide for Northeastern North America by Jessica L. Allen and James C. Lendemer. I used A Color Guidebook to Rocky Mountain Lichens by Larry L. St. Clair to assist with identification. A free PDF is available (legally) here.

UPCOMING COMMUNITY SCIENCE EVENTS

Today, Monday, February 17th, is the last day of the Great Backyard Bird Count. You still have time! For just fifteen minutes, track the birds you see and hear wherever you are (it does not literally have to be your backyard) and enter your checklist into eBird.

Next weekend, February 22 and 23, the Georgia Botanical Society is hosting a field trip to Stone Mountain Park to see trout lilies. The only cost is the parking fee that the park charges. In the Atlanta area, trout lilies should be in bloom next week — a sign that spring is truly on its way.

Gorgeous pictures of the lichens!

Thank you for the teaching and beautiful photos!